Here’s a link to Guatemala’s Golden Midwife, a fascinating and informative article by Catherine Porter of the Toronto Star, mostly about traditional birthing practices among indigenous women in a rural area in Guatemala, but also about the complexity of modern life for many Guatemalans.

SAN JUAN OSTUNCALCO, GUATEMALA—Another woman arrived early this morning at Ruth Ana Maria Perez’s house, across from a small corn field on the very edge of town.

She lies now in Perez’s concrete, purple front room, on a green plastic mattress tucked into a turquoise wooden bed. It is cold and damp; the rain pours down every afternoon. Perez checks her pulse, pulls a needle from a box in the glass cabinet near the bed and, after filling it with rociverine (a muscle relaxant), she pokes it into the woman’s exposed haunch.

“She’s five centimetres dilated,” Perez says. “This will help open her faster.”

Dona Ana, as she is known, is the most successful midwife in town. She delivered her first baby at age 11, when her mother — a midwife — was too ill to get out of bed. Since then, she has ushered 11,000 souls into the world, up to 10 a week during a full moon.

Her success glows from her mouth — a row of gold stars embedded in her top teeth. Her butter-coloured two-level house is grand by local standards. There are two cars parked out back. And she can afford the cabinet of swabs, medication, surgical scissors and latex gloves.

She has never been trained to use any of it. Nor was she trained, formally or informally, to attend births. Like most Mayan midwives, Perez considers her midwifery a “don” — a skill she was born with.

***

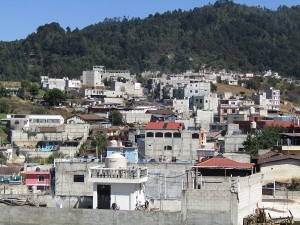

Almost 500 years since the Spanish infantry conquered the Mayan K’iche’, Guatemala remains a divided country. There are the Spanish-speaking Ladinos, with their jeans, light skin and briefcases, who live in the southern cities. And there are the Mayan descendants, who live in the north and western highlands, tilling the milpa — corn fields — in their skirts and huipels. They speak their own languages — 21 Mayan languages are used in Guatemala — and retain many of their customs and beliefs, including those of medicine.

For Mayans, illness results from imbalance, often between hot and cold. Their main curative is the tuj — steam bath. They are behind most houses: waist-high, made of mud bricks or cement, with just enough room inside for a bench and fire. The tuj is considered especially important after birth, when a woman has lost much “hot” blood.

It doesn’t matter how well-equipped or even beautiful a hospital is — the regional San Juan de Dios hospital in Quezaltenango is sheltered by whispering pine trees — for many Mayans, it is a symbol of colonial oppression.

Even Mayan doctors I spoke with say they feel degraded in Ladino hospitals when they arrive as patients. They are made to change into thin hospital gowns, showered, and then taken to a sterile birthing room to deliver their babies alone, without the support of family.

That’s standard practice, the obstetricians at San Juan de Dios told me. But, the Mayan women don’t understand. Despite the prominent sign declaring every pregnant woman will be treated in her own language, doctors acknowledge none of their colleagues speak Mam, the predominant language of San Juan Ostuncalco. The sign is written only in Spanish.

***

[Dona Ana’s] current patient lies corpse-quiet in the turquoise bed. She whispers that her name is Lorenza Augustin. She’s 33. She is from Las Barrancas, the canyons — a rural village two hours away by twisting dirt road. Her family farms corn and squash. She has never been to school. She speaks only Mam.

This is her fourth baby. Her three daughters were born in her bed at home. A urinary tract infection early in this pregnancy spooked her family. They decided going to Dona Ana, with her Western medical supplies, would be safer.

They are hoping for a boy.

“Aye,” Augustin says softly, as Dona Ana massages her hips to ease the pain and get her to dilate faster. It’s her version of an epidural — her glass cabinet contains no pain medications.

Dona Ana pulls a chair beside the bed and waits. The room is quiet. A wall clock ticks. Augustin’s breath quickens to a pant during a contraction and then falls silent again.

“She’s very brave,” Dona Ana says.

***

Two days later, Augustin is back in her own bedroom, resting beside her baby in one of two double beds. Her mother-in-law and nieces flit around, bringing cups of hot chocolate and bowls of beef broth. These are considered “hot” foods by Mayans, unlike green vegetables and white meat. For 40 days, while she recovers, Augustin will only eat hot food.

She will stay in bed for that entire time.

The house, which overlooks a lush green valley of trees, is as big as Dona Ana’s. Husband Rogelio Delgado built it with his brother five years ago, using money they had saved while working construction jobs illegally in the United States.

It took him a year to pay off the debt to his smuggler after his first clandestine trip to California eight years ago. Since then, he has snuck across the Arizona desert twice more, sending money home every month. He shows off a large American fridge in the kitchen — a real luxury here — and a bathroom shower, both of which he shipped from California.

Both came at a price.

“My third girl, Sandra Valeria, she was 5 weeks old when I left the last time. When I came back, she was more than 5 years old. She just knew me by my picture. She didn’t come close to me for 15 days,” Delgado says.

The family tuj is next to the driveway. Augustin’s mother lit a fire in it last night, and boiled a giant pot of water for her newest granddaughter’s first sauna. Then, Augustin and her baby went inside together.

The baby still hasn’t been named.

“We are thinking about either Kimberly or Lorenza, like her mother,” Delgado says. The extended family will decide together.

Two things are certain. Her life will be much more comfortable than her mother’s. A school has been built down the valley. Her sisters walk there every day. Her world will expand beyond the milpa, where her mother started working at age 5.

Second, she will grow up in a household of women. Delgado is planning to return to California soon.

ShareThis

ShareThis

ShareThis

ShareThis